Image Series: Rising Waters

Who knew I would make a documentary?

I enter into most projects with a substantial amount of prior planning. Sometimes, however, you have to just adapt to what nature and chance provide you. Cape Cod is a wonderful place, but for most of the year it is choked with traffic and tourists. I often go in early spring, especially when nor'easters bring heavy snow to Boston and rain to the Cape. This year has been especially stormy, due to unusual conditions in the Gulf of Mexico and in the Arctic. The Gulf waters are unusually warm this year, providing large amounts of humidity to fuel big storms in the American Midwest and East Coast. In addition, a huge surge of warm air invaded the Arctic, making it warmer than Sweden. The result in Europe was "The Beast from the East", a powerful storm moving backwards from Siberia into Great Britain. For the US, the cold air displaced from the Arctic formed a blocking high pressure dome east of Greenland. This meant that for two weeks the big storms generated by Gulf moisture were blocked by the high off Greenland. Cape Cod endured hurricane-force northeast wind gusts and large waves for several days in a row. Unfortunately this coincided with astronomical high tides to cause massive beach erosion.

For me, the bad weather simply meant too many days indoors, so I booked a room on the Cape for two days (March 9-10). I wasn't out for anything particularly special, other than some much-needed exercise. I took my trusty crop-sensor Sony, a macro lens, a simple wide-angle, and a general-purpose zoom. As I began to visit sites on the Cape, I quickly realized that I was there at a critical point in coastal history. Even though I don't consider myself a documentary photographer, I realized that there was a story here that needed to be recorded.

For three days of astronomical high tides, the Cape was pounded by relentless northeast winds. Enormous amounts of ocean water were pushed into Cape Cod Bay. 25-foot waves pounded the eastern coast, open to the Atlantic Ocean. Winds gusting to 97 mph caused some tree damage, but the Cape is used to such winds. The first beach I visited was Head of the Meadow, on the east coast north of Truro. The parking lot was mostly covered with sand, but there were a few spots to park. A small sign stated that the beach was closed and people could enter only at their own risk. The beach was mostly gone, as far as I could tell. I was there at low tide and could record some waves coming in. The next place I visited was the Mass Audubon Wellfleet Bay Sanctuary. This is on the bay side of Cape Cod, so it escaped the big winds and waves. However, some of the trails were littered with debris that floated in on high tides. The trail goes down to a salt-water marsh that, by definition, floods at the highest tides. As the trail neared its low point, Mass Audubon had placed posts indicating where recent estimates showed the high tide line would be in the future. I happen to know that the very latest research shows that these dates are too optimistic. Still, it was a warning of what changes we must adapt to in the near future.

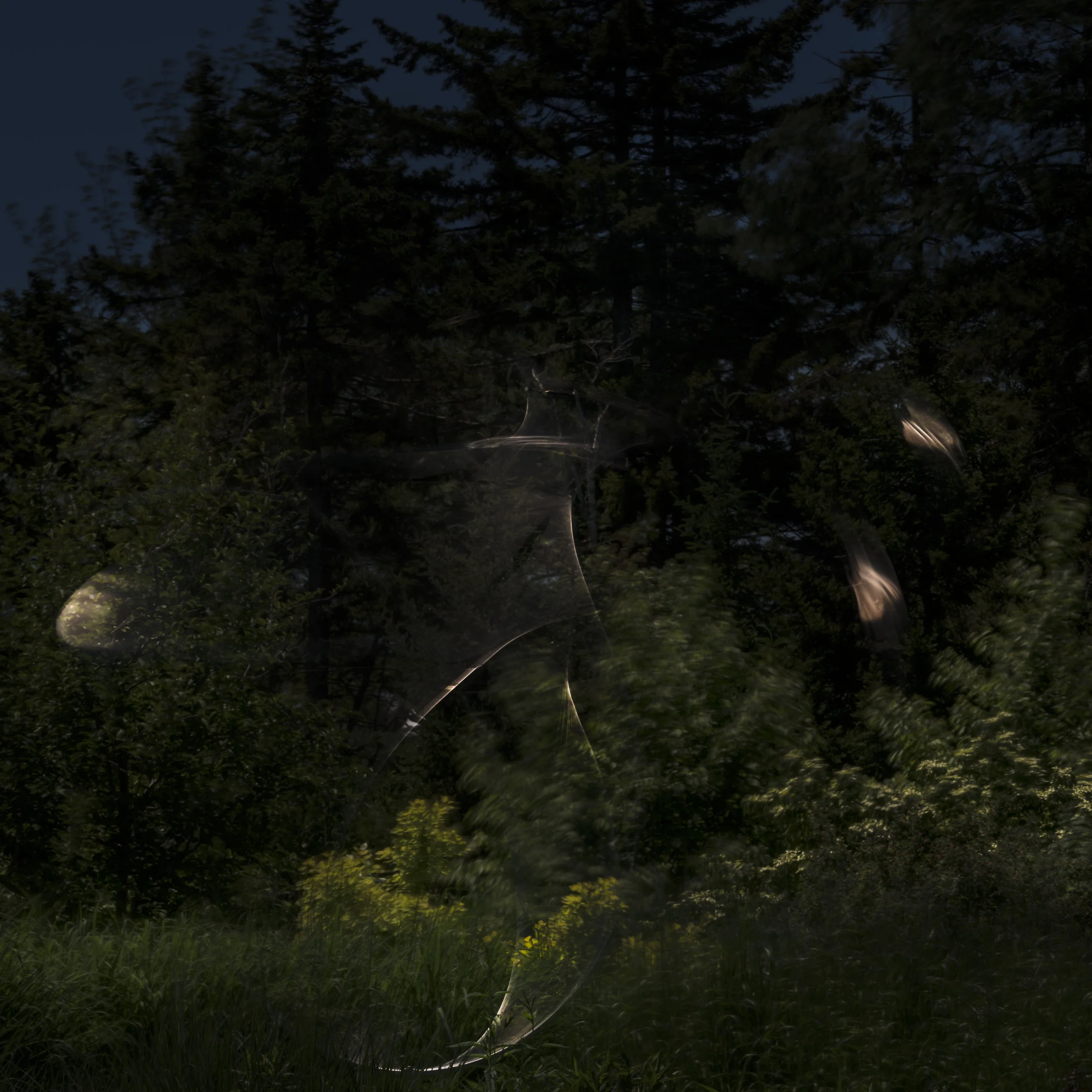

On the second day I decided to trace the Pamet River, which starts in some kettle ponds on the eastern side of the Cape near Truro. The river then meanders west and empties into Cape Cod Bay. It is an important fresh-water ecosystem for the outer Cape. Although the river's headwaters were close to the eastern border, there was a comforting 40-foot high bluff between it and the open Atlantic. I looked the area up on Google Maps. The satellite images showed a distressing looking circle of sand where part of the bluff used to be. This "dune blowout" covers several acres and spills into one of the headwater ponds. The parking lot is almost all gone under mountains of fresh sand. I found some historical documents that showed a minor "blowout" in 2011. Local community groups were hopeful they had it under control with innovative fencing and dune grass replanting. All of that is simply gone. I took some pictures on the blowout area which show substantial amounts of water had recently been washing over the entire breach and into the Pamet River.

If a channel forms, which looks to me like one more storm into the future, the differentials in water level between the open Atlantic on the east and the Bay on the west should start rapidly scouring a deep channel. At that point, Provincetown will be geographically on an island. (Disclaimer: I am not a certified expert on all this.)